Sam was born in the summer of 1990, the year Beth turned 36 and I turned 40. We have two daughters who turned 14 and 11 that year, so Sam was a late arrival into the family. We would wait 27 years to learn that a de novo mutation of the KAT6A gene on one of his chromosomes accounts for his many early and continuing developmental deficits and mental challenges.

It is now 2021, and in cleaning out some old boxes recently I found a photocopy of a handwritten letter that I had sent to a friend in April of 1991 when Sam was not quite eight months old. A quarter-century later I don’t remember having written it, and yet, it’s the best account of his first few months that we could hope to find. Edited a little for brevity and with paragraphs numbered so I can refer to them afterward, I’ll let the letter speak for itself:

* * * * * * * *

1) I’m surprised at how hard it is to write this. It’s easy when there is nothing much to say — when everything stays the same. But, in the first place, you’ve had some very difficult changes in the last year or so, and now we’ve had some rough and challenging times.

2) When your letter arrived in December we were having a struggle of our own. Ruth, our 14-year-old, had just undergone knee surgery in November to correct some damage done when she was hit by a car in July. She has congenital knee problems anyway and had already undergone surgery in the other knee two years ago…

3) Sam was born last summer and, unlike our two girls, he was 5-6 weeks premature. He lallygagged in intensive care for three weeks just to get the hang of eating and getting his body temperature regulated.

4) When we finally took him home we assumed everything was going to be fine. But, in November, we decided to take him to an ophthalmologist just to check his uneven pupil size, which he’d had since birth. We left the doctor’s office assured that there was nothing to be concerned about. Around the time your letter arrived in December we were saying to each other: We know he’ll be a little behind for a while for being premature, but at three and a half months old shouldn’t he be looking at faces?

5) We pondered this question for a week or so and then he distracted us by starting to have seizures in January. So Sam and Beth and I spent a week in various hospitals. We talked about writing to people then, but so far all we had to tell anyone was how uncertain things were with Sam and how confused we were.

6) We were back in the hospital for seizures later in January, then, in the first week of February, we took him to the developmental clinic at Eastern Maine Medical Center — something he was eligible for at six months of age due to being in neonatal intensive care at birth. We’re not naïve people, really, but we went to the clinic expecting to come away with a clean bill of health.

7) Up to this point the seizures had no known etiology. They had done a CT and an EEG, both normal. Two doctors said epilepsy and two others said breath-holding. At the developmental clinic in early February we were knocked down another notch: asymmetrical motor development, serious developmental delay, no muscle tone in trunk or limbs, and little if any visual tracking. They didn’t diagnose cerebral palsy at that point but that’s what it all suggested. Actually if that’s what he has — and it’s a kind of catch-all diagnosis — he may be a year old or more before they make the diagnosis because it’s so circumstantial.

8) The staff at the clinic is excellent and they have looked after us. Of course, he had more tests that day including another EEG. We went home with a bunch of literature and began reading it.

9) Then one day shortly after that I came home from work and Beth said she’d made a discovery: If she treated him as if he were blind and if she looked at his whole situation that way, it all fit. (I was the one who, in December, kept asking, Why doesn’t he look at me?)

10) And yet, he’ll fool you. He’s just as bright-eyed as any other kid. The ophthalmologist in November declared his eye structures normal and ought-to-function. And sometimes he seems to look.

11) We called the doctors back. Take him to Boston, they said. We did, a month ago, in mid-March — to a pediatric neuro-ophthalmologist. No visual activity, the Boston doctor said. He doesn’t see. The diagnosis, for the record, was “blindness, no specific degree.”

12) I had already been in touch with the state agency that deals with blind children, so as soon as we were home we contacted them again. And even though the Boston doctor said there’s no therapy for it, a teacher has started working with Sam and has showed us that he can see light (lights) and bright contrasts. Apparently, however, it’s very weak. The teacher disagrees about visual therapy — a classic disagreement between the medical professional and the laity.

13) So now, at seven months of age, we’re taking him into a closet two or three times a day with a blacklight, fluorescent posters, a flashlight, and a flickering bulb. We reward him when he turns his eyes to “localize” on a poster or bulb. We want him to reach for what he sees, so positive reinforcement is important.

14) That leaves us with the question: Is he developmentally delayed due to the blindness — he fits that possibility, or is he blind as part of a larger package of developmental problems? We may be a long time in finding out.

15) Sam is the only blind infant of record in the state of Maine right now. His teacher has about 16 other students in three counties, and I think there are over a dozen itinerant teachers in her field in the state. The other students range up to 21 years of age.

16) But none of this yet tells you what he’s like. In spite of it all, this boy is an absolute joy. He laughs at everything. He sits in his walker and feels the toys on his tray. A week ago he found one of his thumbs, so now the thumb is either in his mouth or cocked at the side of his head the way some people will hold a cigarette. He likes to test textures and definitely has some favorite toys.

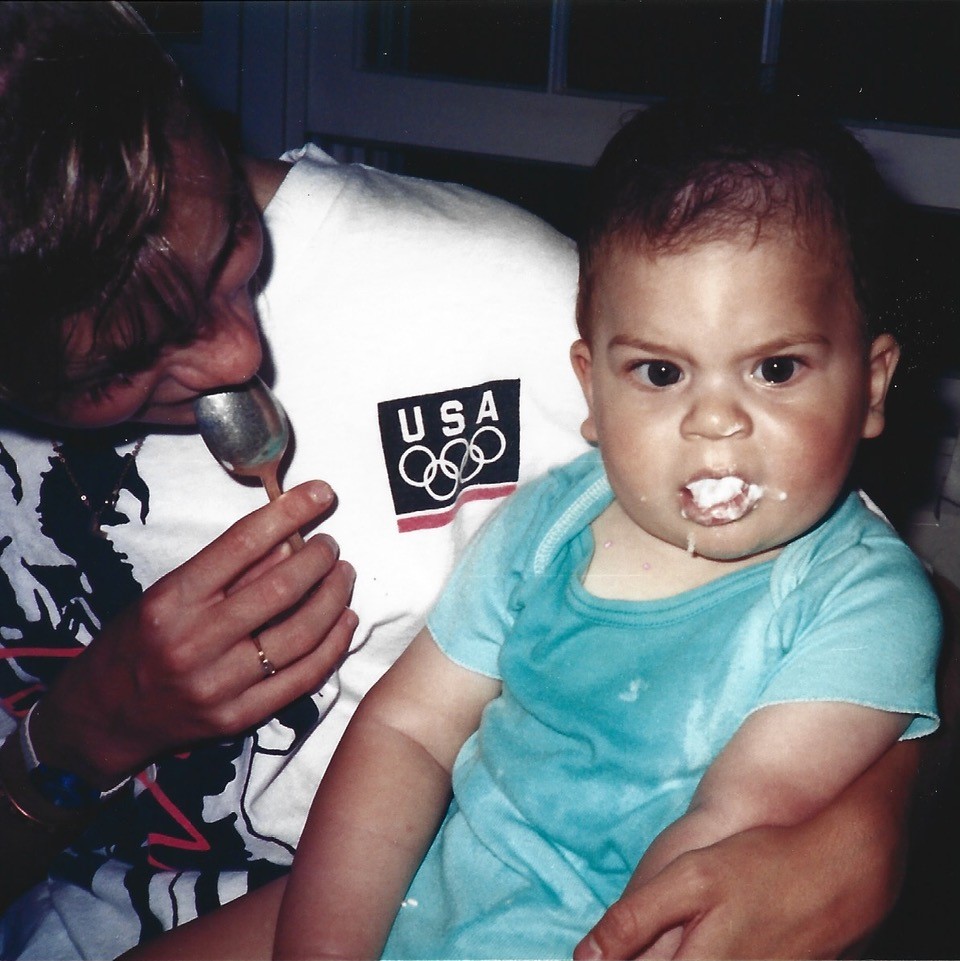

17) Once we began to treat him as blind and to concentrate on teaching his other senses, he has made noticeable progress. He’s alert. He “talks” to his toys. He eats baby food and opens his mouth for the spoon.

18) He definitely knows his parents and his sisters, mostly by voice probably, but also by the way each one holds him and by the things he knows each one of us does with him. (I play rough. He splits a gut at things like “falling down” and “don’t bump your head,” playing “boo,” and such.) He doesn’t quite sit alone, but we think it’s coming. Since the developmental clinic in February he’s had a physical therapist as well. And he responds to her well. He wants to please us.

19) He listens intently all the time and loves certain sounds. A tinkling bell gets him laughing or smiling. Music is magical. He loves it when someone whistles. Certain of his rattles are his favorite toys, and he can locate and pick them up from a tray in front of him.

20) He’s enormously popular whenever we take him anywhere — with his thick, curly black hair he’s the most handsome boy most people have seen in a long time. He’s around 18-19 pounds and can pass for someone much younger. It gets awkward at times, though. Strangers are caught off guard because he doesn’t appear to be delayed or blind.

21) Ruth is recovering from the latest knee surgery but her surgeon thinks she will always have problems with it. She can forget about high-impact sports. Leigh has braces, plays junior pro basketball, and generally has a very good life. (Classic middle child?)

22) Leigh and Sam are constant companions. A little too constant at times, but I try to do a lot with him to relieve her of his presence.

23) Beth and I are scheduled to go to Ogunquit April 26-28 (without kids!) on a weekend retreat for parents of handicapped children. Your tax dollars at work at last!

* * * * * * * *

COMMENTS

Sam’s Sisters

Paragraph (2) mentions Ruth’s knee problems. She is 45 this year and is finally facing the prospect of knee replacements, both knees. But she has led a happy and fulfilling life on her original knees up to now. Sam’s sister, Leigh, now 42, is the mother of two little girls that Sam adores. By the time she was 13 or 14 Leigh knew that she was going to make a career of educating special-needs children. She went straight for it as soon as she finished high school and now holds two masters degrees, in psychology and in applied behavior analysis. In her work she is a consultant in the school systems around Bangor, Maine.

Cortical Visual Impairment

In Paragraph (4) of the letter, and then resuming in (9) through (15), I discussed Sam’s apparent blindness. In 1991 we had no idea that there was such a thing as cortical visual impairment. Coincidentally, in 2018 and near the time when we first learned of CVI, I read a book, Crashing Through, by Robert Kurson. It’s the story of a man whose corneas had been destroyed by a chemical explosion at the age of three.

Decades later, in the 1990s, he was a completely blind husband and father in his 40s, fully content and successful in business, when a friend who was also a doctor suggested he undergo stem cell transplant surgery in an innovative procedure to restore his vision. Since his lenses and retinas had not been damaged in the accident, the prospects for success were good.

The surgery was successful. However, even after months rolling into years of rehabilitation, his brain failed to make any useful sense of the information his eyes were providing. He could discern general shapes and motion, and he had sharp visual acuity, but he could not make sense of printed words or tell one face from another. After months of rehab he could still not recognize his own wife’s face.

The point is, in his early development after the accident at age three, in the absence of eyesight, the man’s brain had repurposed his visual cortex for other functions. The new neurological input from his optic nerves simply did not compute.

This man’s story gave me considerable insight into the problem of cortical visual impairment. When Sam was around three years old he had a visual evoked potentials exam. Electrodes were attached to the back of his head to record brain responses while the technicians applied visual stimuli such as lights of various intensity and duration. The impulses had no effect — they did not reach the visual cortex.

This is even more confusing, because by that time we could tell that Sam could see, in a way. Evidently — and we’ll never at this point know how — visual information provided by his optic nerves is going to a different area in his brain than normal. As one doctor at the time suggested: Visual impulses are going to his brain’s auditory center, auditory signals are going to his olfactory center, and so on. This is just a hypothesis, of course, but if he is smelling sounds and seeing odors then that could go far to explaining his strange reactions to stimuli.

We know that Sam can see something. We call him Rocket Arm for his ability to suddenly reach out and grab an object in his peripheral vision. And that points to a couple other aspects to the mystery. For the rest of us, our center vision is processed in a different part of the brain than our peripheral vision. The brain then coordinates the two and, as we know, erects the image which is presented upside down on our retinas. Sam’s peripheral vision may in fact be normal if it is processed like anyone else’s. It may be only the optic nerve impulses from his center vision that are processed in the wrong area and are not understood as visual, leaving him impaired. He rarely looks directly at anyone or anything. And apparently he has no depth perception. Is the image, if there is one, from the center of his vision perhaps upside down as well?

Seizures

In Paragraphs (5) through (7) I wrote about seizures. I made a short video of one seizure when he was a few months old. He is crying fiercely while lying on his back. As any baby does, he expels air during a long, silent pause. Normally a baby then inhales a great lungful and then wails again, but in the video Sam just keeps expelling (or holding on the exhale) until he apparently passes out. Up to then, as he cries, his hands are in fists, his arms and legs are extended, and when he passes out his legs stiffen as his arm curl toward the front. Each time this “seizure” happened he would pass out for at least a half hour. After a while he would either wake and cry some more, wake and seem confused, or simply remain asleep for a long time, breathing normally.

The seizures weren’t frequent — not daily, for instance. They would happen during a spell of intense crying, as if he were in intense pain. But from what? While the seizures weren’t a daily event, something did seem to cause him severe pain daily. He would be resting happily in a baby seat and all of a sudden he would utter a piercing shriek and begin crying as if he’d been stabbed. We were able eventually to associate the sudden pain with GERD, or gastro-esophageal reflux.

Gastro-intestinal Distress

Little did I realize in April, 1991, when I wrote this letter, that only two months later Sam would be having a consult for reflux and a GI series at Maine Medical Center. Shortly after that consult he was admitted for surgery to correct a malrotation of the duodenum, the first section of the small intestine just after the stomach.

At the age of 10 months, then, Sam was released from the hospital with a nissen fundoplication — creating a one-way valve between the esophagus and the stomach, and a gastrostomy. The fundoplication prevents reflux but also prevents air from coming back up. In other words, he can’t burp and can’t vomit. The gastrostomy permits venting air from the stomach through a G-tube and has permitted feeding him a liquid diet ever since. For years venting and feeding was a constant, full-time occupation for one or both of us.

For a few years Sam tolerated baby food but eventually refused it altogether. We pumped Pediasure into him through the night for several years until he could take all his sustenance through the tube by gravity feedings. Since his last taste of baby food as a second- or third-grader he has been entirely tube-fed, graduating from Pediasure to Jevity as an adult.

Sam has been back in the hospital many times and has had followup surgeries for a volvulus, a repair of his nissen fundoplication, a pyloroplasty — a severing of the sphincter separating the stomach from the duodenum, and other gut-related problems. He has been pretty stable in that area since reaching adulthood, though.

Sitting and Walking

In paragraph (18) of the letter I mentioned sitting. I also touched on his laughing and added that he had begun seeing a physical therapist. By age two or so he was crawling, but before long his preferred mode of propulsion involved sitting and scooting sideways by raising himself on his hands. He would take the weight off his butt and drag his legs while pulling himself along sideways with both hands at once. (He still does this now and then and can move quite quickly when motivated.)

In time, the physical therapist working with him insisted that he should practice walking like anyone else. So by age four or five he was using a tiny walker that wrapped around behind him. It had cogs to prevent it from rolling backwards, and so as he walked we would hear the clicking of the little metal tabs that lay behind the rear wheels and engaged the cogs.

Sam wore a helmet (willingly) whenever he used the tiny walker. He won’t wear anything on his head or hands any more, summer or winter, and also refuses a mask. That makes it difficult in situations now, such as doctors’ offices and hospitals, where there is zero tolerance for non-compliance.

In his younger years we attended a local church regularly, all of whose members doted on the skinny, ever-smiling little boy. We’ve since moved to another town, but in that first church Sam became accustomed to the routines, including the weekly trip to the communion rail, where he would always stand for the priest’s blessing. One Sunday morning, when he heard the usual sequence of music and activity leading up to communion, Sam stood up in the pew, halfway back in the church where he was seated next to the center aisle, reached for his walker, and, for the first time, walked the length of aisle by himself. Everyone else was still seated. The front rows had not even begun to move to receive communion yet, but Sam was on his way. We let him go, and he slowly click-clicked himself the entire distance without stopping. The congregation remained silent through his procession, but there was literally not a dry eye in the house. Our priest responded appropriately, and it has always been about the most poignant moment for us in Sam’s life.

From kindergarten through about fourth grade Sam did walk in order to get most places. He always had a walker of some kind but could let go and take several steps unaided. By the fourth grade, though, he had begun to regress to needing the walker full-time. Two factors seemed at the root of this turn-around. He was growing tall enough that his center-of-gravity had shifted more from his hips to his chest and shoulders, and he had begun to fall more often. One fall at school was particularly dramatic, resulting in an E.R. visit and sutures in his head. Around the age of 11 he began suffering bone fractures due to slips or falls, due to osteopenia and later, osteoporosis. With reduced time on his feet after that, along with hypotonia and related delays in his physical development, he now lacks the strength in his legs to remain steady while standing. He gets around mostly by wheelchair and walks with assistance primarily to transfer short distances.

Music

What amuses Sam is often something generally pleasant enough in itself but not what anyone else would consider funny. So when he suddenly laughs, it tickles us that he did, and so we laugh with him. He does like pratfalls and slapstick, exaggerated play and pantomime, gross noises and gentle teasing, as long as none of this startles him. As a toddler he seemed frightened by the sound of paper bags, for instance when we would be unpacking a load of groceries. He overcame the apparent fear eventually, but the crinkling of heavy paper still excites him. We would often give him a large empty bag to crinkle himself, and when he was in his teens he would utterly destroy it in the span of half an hour.

Music is magical, I said in paragraph (19) of the letter. With my own intense background in classical music I have often played for him my favorite melodic pieces. Sam listens to any kind of music, but he sometimes “sings” along with a piece that pleases him, and there are several songs which, we have learned, will trigger a deep emotional response in him. Some, which have affected him since earliest childhood, almost make him cry (although his crying is not a teary-eyed sobbing).

Sam is a good rider in the car, which has made it possible for us to take several cross-country road trips (before the pandemic). We haven’t taken him on a commercial flight since he reached adulthood, but he was a good flyer. The security procedures since 2001 have made it impracticable to fly with him. I think 2005 was the latest year in which we attempted it. Before then, though, he had flown with us to Florida, Aruba, and Ireland.

In the car, if we forget to turn the radio on, he will let us know from the back seat by clapping his hands. When music is not playing and the TV is not on Sam sometimes makes his singing sounds when he is most happy — that is, he makes a sweet, high-pitched and sustained squeaky sound with his voice. He will sing while sitting beside one of us and holding our hand. He doesn’t normally like to be hugged but will sometimes accept a hug and sing with it. He often briefly sings alone in his bed right after being tucked in for the night. We cherish these times. They confirm that all is well with him for the moment.

Sleep

Not mentioned in the 1991 letter but related nonetheless, it’s necessary to mention that Sam sleeps poorly, as if the neurological pathways and hormones to promote sleeping have not developed in him. He would never take naps in the daytime, right from birth. One evening, at around age five, he became so afraid to lie down and so terrified to close his eyes that he stayed awake for two weeks straight. He could not be cuddled or consoled throughout this time. He crawled from room to room day and night. He refused to sit in one place. We could not lay him on a couch or a bed; he merely fought it and cried.

All through the daytime he might be calm at times but wary. As darkness began to fall every evening he became agitated and frightened again. At one point during this period he was in intensive care at the local hospital and was given ten times an adult dose of valium, which had no effect.

Our daughters were old enough to carry on independently and did so, but Beth and I had to take turns sleeping, because one of us needed to stay up all night with Sam.

The whole thing resolved as abruptly as it had begun, but with the residual effect that Sam has never since then been interested in sleeping and needs a sleep aid every night to ease him out of consciousness.

Speech and Language

At age three Sam was diagnosed with autism. His behavior was then and remains consistent with the diagnosis. In the early and mid-1990s it was a diagnosis that assured as much attention as possible in school. After his third-grade year we moved from one small town deep in the Maine woods to another. Both school systems were terrific about addressing his needs, although services did not come without a great deal of advocacy and participation on our parts as parents.

From his pre-school years through several years of grade school Sam had a speech therapist. He makes many vocal sounds, some of which have meaning which we understand — hoots and groans and gentle tones, but as for speech, he never succeeded in anything more than an accidental syllable now and then. Therefore we included training in early versions of touchscreens that gave feedback. He does seem to distinguish images and color zones on a touchscreen but still makes mostly random taps in the areas that will give feedback.

He also made progress using PECS — a picture exchange communication system. Used mostly at school, he was taught to exchange a picture of something or someone for the actual object desired or person being discussed. Two problems impeded progress with this, though: his visual impairment in distinguishing between photos, and intent, which is to say, if he didn’t want it in the first place, why ask for it with a picture?

And we included lessons in American Sign Language in his early speech training. From ASL Sam did pick up one sign, which he has adapted to many uses. The sign for “more,” touching the fingertips of one hand against the fingertips of the other, is now his sign for “yes” and “I want” and “give me.” It is his sign for anything that affirms a desire for something but is now simply a clap of hands, but it means he wants something, even something that hasn’t been offered, such as music in the car while riding. He does respond to the sign for “no,” which we still use with him sometimes.

Sam has phenomenal hearing and uses it over his other senses. He pays attention to conversation in other rooms. If he is sitting on a couch, he regularly lies down flat as soon as someone in another room touches one of the items used in his six-times-a-day feeding routine. We aren’t even aware that we have made a sound, but he has been listening for it.

His receptive language is very good and even though, with autism, he often chooses not to comply, he knows what we are asking of him. He gets excited when we mention that his nieces are coming to visit, for instance, and he responds appropriately, although sometimes to our amusement, when we verbally put choices before him.

So Much More

I meant for this article to cover the 1991 letter and the topics that it raised. There is so much more about Sam that I could expound upon here, but maybe those thoughts are better saved for another time.

Where Sam is in his thirty-second year, from our present viewpoint all that we went through in those early years is terribly compressed. Beth and I held ourselves together somehow, as two survivors of a shipwreck might bear one another up while grasping for flotsam to cling to. Nothing else mattered when we were dealing with his care and needs early in his life, although I did need to hold onto my job.

Sam was unique — within the small towns where we lived, within the experience of our insurance plans, even within the state. When he was two, Beth was appointed to the Maine Developmental Disabilities Council and within a couple of years was elected chairman, a position that she held for a few years after that. We — especially Beth — became resources to other parents of special kids, parents struggling with insurance and school systems and medical resources. We have always had good family and community support systems ourselves.

By the time Sam was six years old we had begun taking special needs foster children, some of them for years at a time and mostly two at a time, and today we remain guardians of one, living nearby, while another is raising a family just around the corner from us. Both of those girls have been Sam’s sisters for more than twenty years now.

We live now with our own version of PTSD, partly from the foster parent experience I suppose. We love our children and feel especially protective of the ones who don’t have their own “bootstraps.” We are scarred and hardened and pretty intolerant of institutionalized ignorance. We’ve had to educate doctors and bureaucrats and we’ve encountered plenty of quackery along the way. Throughout the past decade, though, we have been blessed to be working with a team of outstanding doctors, agencies, and professionals even given our remote location.

We adapted the house that we have lived in since Sam was ten years old by adding a suite for him and making the house fully accessible. At 67 and 71 Beth and I remain healthy and vigorous, even as we deal with some common effects of aging such as coronary artery disease and stents, glaucoma and macular degeneration, and relative isolation in a splendid forest wilderness. Looking back, I can say we wouldn’t have it any other way.